S01E04: A sort of homecoming -- Arriving in Baile Dhá Thuile

Votive candles, scalding-hot instant coffee ... and trifle.

Welcome to the third instalment in what started out as a very short story about my somewhat muddled family history journey. In the first instalment, I discovered that my Irish ancestors, whom I’d been led to believe lived in County Clare, actually hailed from the tiny West Limerick village of Baile Dhá Thuile. In the second instalment, I learned that my great-great grandparents, William and Johanna, emigrated to Australia in 1855, leaving their infant son, Richard, in the care of his grandmother, Elizabeth. And now, on with our story …

AN ABSOLUTELY ORDINARY SHERRY TRIFLE • On my very last night in Ireland in 2023, I was sitting in the servants’ kitchen of Shankill Castle—a stately manor house just outside of Kilkenny—enjoying a “slap-dash meal” that was more sophisticated than anything I’d ever tasted in my life, when my host, an Irish painter named Elizabeth Cope, asked me a startling question:

“What is your opinion of trifle, David?”

I paused for a moment, unsure whether she was joking, but then considered the question in my own pseudo-thoughtful way.

“Why, trifle is the prince of desserts,” I replied, finally. “Isn’t it?”

From Elizabeth’s satisfied reaction, I knew that my answer was correct.

It’s not as if I needed anyone’s validation: I’ve known that trifle is the world’s finest dessert since early childhood. I probably even had an inkling of its greatness while still in the womb.

Perhaps this was a question Elizabeth put to all of her guests.

Or maybe she’d caught a glimpse of the single-serve sherry trifle in the box of provisions I’d hauled up to my room.

Whatever its genesis, Cope did not serve me anything resembling trifle that night, although no doubt we both wished she had. Instead, I returned to my quarters and scoffed that single-serve slice of heaven in peace. And then passed out in my own private four-poster bed.

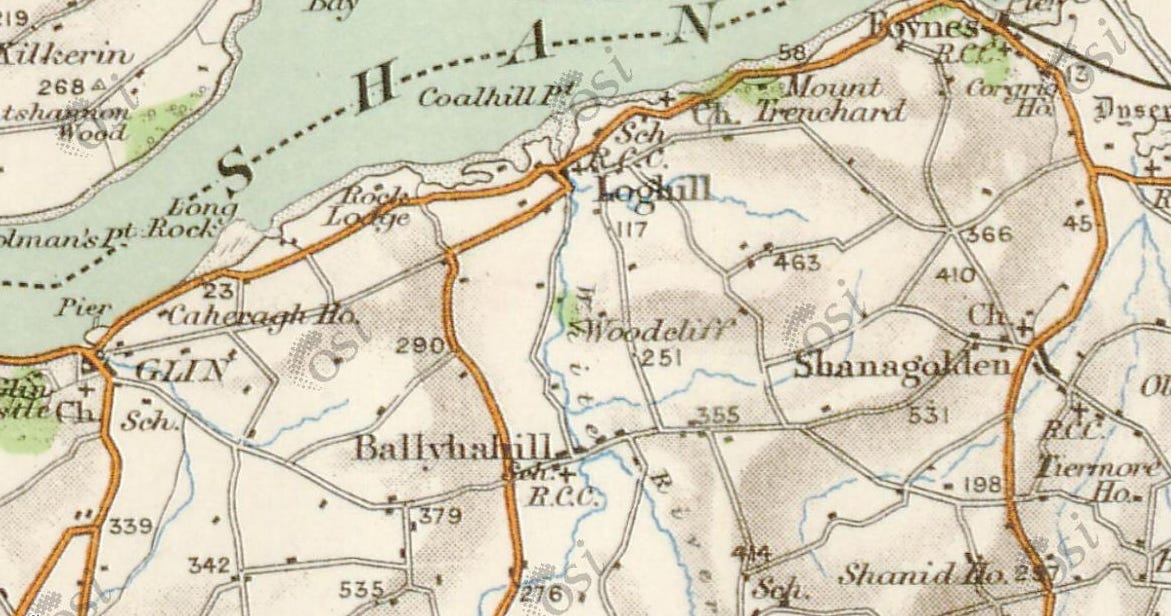

WHERE BEAUTY MEETS DARKNESS • The Dutch have a wonderful phrase to describe a downpour: het regent pijpstelen [literally, it’s raining steel pipes]. I had occasion to reflect on this metaphor when I arrived in Baile Dhá Thuile in the pouring rain, having driven from the genealogy centre in Croom to Foynes (where the seaplanes used to commence their transatlantic flights) and then Loghill, passing fields of rock and mud and gloomy hillsides as I went.

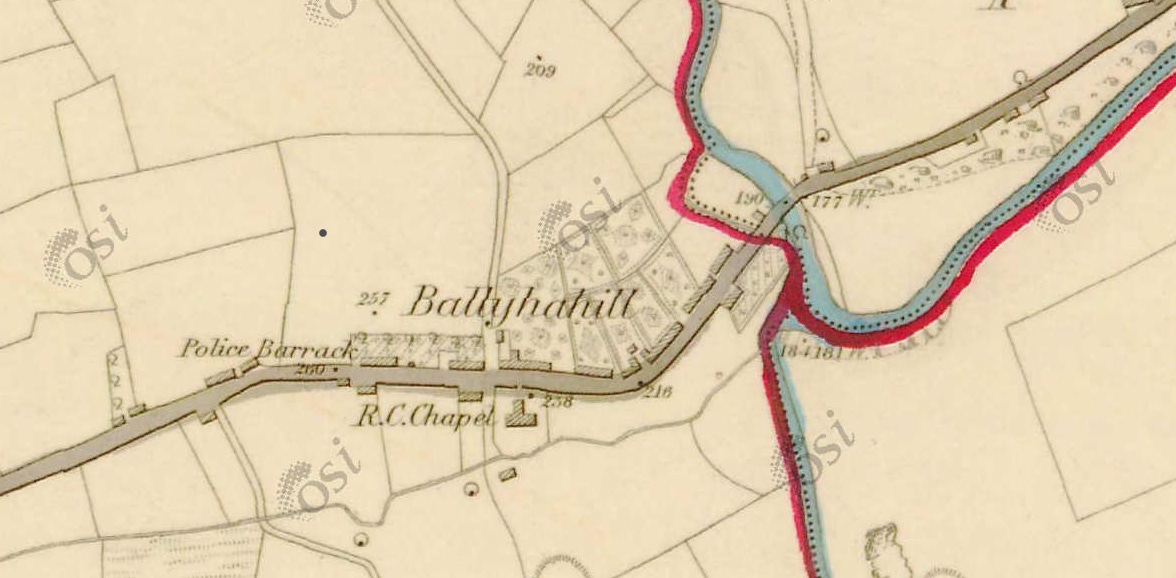

The view of the town from the old stone bridge that crosses An Abhainn Bhán (variously translated as the Owvaun, White or Beautiful River) wasn’t much better: snaking up a small hill was a narrow asphalt road, flanked on both sides by beige- and grey-coloured buildings. As I steered my trusty Fiat towards the town, I felt as if I was on the west coast of Tasmania, or maybe in Cessnock. Oh, did I mention it was raining steel pipes? I mean, it was hosing down.

The river, I noticed, was very full and coursing back the way I’d come, towards Loghill and the Shannon estuary. Was that an omen? Of course it wasn’t! Although, I later learnt that on the far side of the bridge, the main tributary of the Abha Bhán is met by a second, named An Abhainn Dorcha (the Dark River). So, in a way, by arriving in Baile Dhá Thuile in this manner, I was essentially crossing a point where beauty meets darkness, and from which I might never return—at least, figuratively.

Beyond the bridge it was a matter of several hundred metres to the Church of the Visitation, which lies on the river side of the hill. It’s a nondescript building, which has clearly been renovated since my great-great-grandparents were married there in 1853. But still. It reminded me of country churches in Australia: empty but filled with other people’s memories. By the entrance was a row of electronic votive candles, one of which I “lit” for mum, then took a photo to send her via WhatsApp later.

PIGS’ HEADS • Having had enough of sombreness, I exited the church to find that it was still raining cats and dogs (or maybe stoats and badgers) in the carpark. And so, guided by some sort of animal spirit, which seemed to have imbued me with a courage I’d never really experienced in my long years of introspective travel, I stepped onto the asphalt road, boldly crossed the street and entered the P. O’Ruairc Grósaeri: an establishment that does not even show up on Google Maps.

It was the kind of tiny general store I saw everywhere outside the major towns on that trip: a place where you could get your newspaper, pet food, bread, wine, fags or sliced ham. Nothing special about it, expect the name, which lent the place an air of mystique its owner (the mysterious P. O’Ruairc) had doubtless never deserved or intended. After peremptorily inspecting the shop’s meagre wares, I decided to ask the lady working the till if she remembered the Hurleys or the Fitzgeralds.

I knew, from my conversation with C— in Croom earlier, that the Fitzgeralds once ran a store a few doors down Main Street from the present-day grósaeri. So, I reasoned I had nothing to lose, and was also probably delirious from the speed of it all: I mean, just the previous day, I’d been convinced of my origins in County Clare, across the Shannon estuary. Only there I was, in a miniature village shop in West Limerick, inquiring after my ancestors like I was asking the time of day.

“Would you happen to know what became of the Fitzgeralds?” I might have mumbled.

“No, not them,” the lady admitted, with an embarrassed smile.

“The Hurleys, then,” I persisted. “Surely you’d remember that name?”

“Not them either, I don’t,” she may have replied, “but you can ask my husband. He’s back there, slicing the ham.”

I peered towards the rear of the shop, where a shortish man of around sixty years of age was, indeed, handling some sliced meats, or maybe it was a whole leg of ham.

“Can I help you?”

The man (the eponymous P. O’Ruairc, surely?) had a melodious but roughened accent I could barely understand.

“I’m researching my family origins,” I told him. “I’ve just learnt that my ancestors came from Ballyhahill, and that they used to own a store here. Not this one, mind: it was a few houses down the hill.”

“Is that right?” he replied. “What was the name again?”

Just at that moment, a much older woman entered the shop, and moved in our general direction. By the time she reached the back of the store, the woman from the cash register was next to her, and was telling her that I was searching for the Fitzgeralds, and maybe the Hurleys, too.

“Oh, the Fitzgeralds!” she exclaimed. “Sure, I remember them. They used to run the store down the hill. All gone now. It was a post office and a shop. They were posh. Miss Agnes, she was posh. They sold pigs’ heads there, I remember that!”

I’m paraphrasing, of course. I can’t even remember the lady’s name, or her face. But she must have been in her late seventies or eighties. Her claim that the Fitzgeralds had left town 50 years previously therefore tracked but also made me realise I was more than a little late. Had nobody else, in all the time that had passed since 1855, made it to Ballyhahill to ask what became of Elizabeth Fitzgerald and her children and their children? Let alone her abandoned grandson, for pity’s sake?

But, still.

There she is.

THE SHOPKEEPER-BARISTA • The man I have been calling P. O’Ruairc, otherwise known as the owner of the supermarket, may also just have been another man who was working there, or possibly even a fella simply standing there holding a ham. But for simplicity’s sake, let’s say they’re all the same people.

Anyway, this fella said:

“I’ll just get someone on the phone.”

That’s when I noticed they had one of those old-school wall telephones, with a long cord. While he rang the number of that someone, I resisted the temptation to stare at his index finger spinning the rotary dial. After exchanging a few words with the somebody I hoped was someone on the other end of the line, words which I naturally could not decipher, he invited me in to a room at the rear of the store, which turned out to be a completely normal family-home kitchen.

“You’ve travelled a long way,” he said by way of opening. “Can I get you a hot beverage of some sort? Tea? Coffee?”

“I’d love a coffee,” I admitted, although I immediately regretted my choice.

He pulled out a tin of instant coffee, a two-litre container of full-cream milk and a saucepan, plonking the latter on an electric hot plate. This was going to be an old-style 1980s cup of coffee, no doubt about it, direct from the hands of a man more accustomed to boning ham with a long knife than measuring the correct amount of beans for a cortado, let alone warming organic oat milk to the equivalent of the ambient temperature in Dar es Salaam.

I watched with a sort of sickly fascination as he spooned a generous serving of the coffee powder into a giant mug, and then added a dash of hot water from the kettle, mixing them together roughly. While waiting for the milk to boil in the saucepan, we exchanged pleasantries about the weather, and my itinerary. He told me he wasn’t from Limerick himself, but was a Kilkenny man. I could tell that this was meant to be impressive: Kilkenny is a big town, home to about 27,000 people.

Which is 26,850 more people than you’ll find in Ballyhahill, even on a church day.

This kind but gruff man reminded me of my mother’s brother, B—. He didn’t really have time for, or interest in, small talk. Nevertheless he sat with me while I took a tentative sip from my scalding-hot mug of coffee. Thankfully, unlike a “true” barista, he made no protest when I requested sugar, and there may have been a biscuit of some sort supplied and gratefully ingested. Finally, he expressed puzzlement when I told him I’d be leaving Ballyhahill that very afternoon for the wilds of County Kerry.

“County Kerry. That’s … a long, long way from here,” he observed.

“Time waits for no man, etc.” I may have claimed.

But the shopkeeper-cum-barista whose name may have been P. O’Ruairc had a point: having apparently just arrived home, true to form, I was racking off again immediately.

Story of my life.

THE PUBLICAN AND THE CONVICT • After what seemed like an eternity, the liquid in my mug reached room temperature, and I began to drink it. It was not totally awful, and I made a mental note to start appreciating small things in greater quantities. A short while later, a venerable old bloke, who I later learned was the village publican (I hadn’t yet seen the pub further up Main Street) entered the kitchen. My putative host wished me luck and disappeared back inside the shop.

P— was another specimen of the gruff type I saw a lot of during that trip. The type of bloke who’d blend in at a cattle auction in Albury-Wodonga, and otherwise mind his own business on a minuscule sheep farm somewhere above the flooded town of Old Talangatta. I could tell, even at first glance, that here was a man who knew things. No doubt this vibe came with the territory, but it’s also possible to exhibit deep local knowledge without knowing the first thing about pouring a pint.

We sat together at the kitchen table. P— looked away politely every time I slurped from my mug. He was holding a battered Nokia mobile phone that may not have even worked, and kept gesturing with it every time he asked a question or provided me with an answer. We chatted about the Hurleys, in particular. He told me there had only been one Hurley family in the village, but they were all gone. As was the stone house in which they used to live, “over there” (he said, gesturing towards the river).

Then a strange thing happened. P—, who was still fiddling with that brick of a phone, sat up, as if he’d remembered something.

“Now, wait a minute,” he whispered, almost to himself. “Could it—”

I raised my eyebrow slightly at this theatrical trick. What was the man going on about? And then, almost as if to draw me in even further, he began repeating the name, slower and slower.

“Hurley, was it? Hurrrrliiy. Huuuurrrrleeeyyy, wait—no.”

“For Gawd’s sake, man, spit it out!” I may have cried in my frustration.

“I seem to recall—no, that must have been . . . ”

“Hnnnnhhhhhh!!!”

Finally, comprehension dawned in the wizened publican’s eyes.

“Ah, that’s right!” he exclaimed. “I remember now. There was one Hurley fella, who was transported.”

Wait, what??

“Yes, transported,” P— insisted. “He was . . . [pause for extra dramatic effect] . . . a convict. Sent to New South Wales. That’s right.”

“No, that can’t be right,” I told him.

Free settlers, not convicts, mind!

I may have stood up to leave. Ah, who am I kidding? I was riveted, glued to my seat. Transported? What the actual Hendricks? I suddenly needed a drink. But my coffee mug was empty, and I was beginning to feel the effects of the extra large spoonful of whatever P. O’Ruairc had put in there, perhaps while I was busy not looking at his hands.

To be honest, in that moment I feared the worst: that this otherwise pleasant enough old publican was yanking my chain, giving me a bit of authentic Irish convict heritage to make up for the fact that, beyond a couple of birth certificates and the oral testimony of an old woman in a supermarket concerning a pig’s head, my actual Irish heritage could fit within the circumference of the Claddagh ring I was so keen to display on the middle finger of my left hand—crown facing out, mind.

But there was something about his certainty that led me to take a leap of faith.

“Well, gosh that’s interesting,” I admitted, finally. “Do you have a first name for this convict fellow?”

P— said that he would need to make a call, and brought the Nokia into play.

He spoke briefly into the phone and then hung up, informing me that there was another bloke—there will always be another bloke—who would know some more about it, but that today was not a good day to meet him.

“How about I come back on Friday, then?” I suggested.

“That’d be grand,” P— replied, with a smile.

Hurleeeyyyyyyy.

And with that I thanked him for his time and returned to the real world of the supermarket. I located and purchased from the refrigerated section a single-serve sherry trifle, grabbing an extremely cheap bottle of red wine while I was at it.

I then thanked the lady at the till and the enigmatic Mr. P. O’Ruairc. Returning to my Fiat in the church carpark, I settled in for the long drive to Westport, Kerry, expecting nothing but rain, and beautiful darkness, all the way.

POSTSCRIPT • I’ve been overwhelmed by the responses, both public and private, to these posts about the humble beginning of my family history journey in Ireland. I am now hard at work on the next instalment. But those of you who have been looking forward to my exposé piece on the history of the Dutch schuur may have to wait a while longer for that.

As ever, if there’s a specific topic you’d like me to cover in a future post, please feel free to leave a comment (if you’re reading on Substack), reply directly to this message (if you’re receiving the newsletter via email) or else contact me the old-fashioned way at davey@daveydreamnation.com.

All the best and bye for now,

Davey

Ahhh, the plot thickens!!