Poor Richard: One way to get to West Limerick

Literally driving ninety down a motorway towards my ancestors.

In this week’s post I continue the story of my family history journey in Ireland, which began in 2023 and basically hasn’t stopped since. If you need to catch up, read the previous instalment: (It's a Long, Long Way) From Clare to Here.

DRIVING NINETY • It’s a phrase I heard a lot in Limerick: driving ninety possibly refers to the speed at which you’re travelling in an automobile—in my case, a tiny Fiat 500 barely big enough to hold my linguistically ripped frame, let alone my emotional and spiritual baggage—but in Ireland it can also mean going full tilt, living your best life, or enjoying the maximum amount of craic.

Whatever driving ninety means to you, one thing was clear to me: having finally received a clue as to my “true” West Limerick origins, and after four very pleasant days spent slewing and chicaning through the holloways and lanes of County Clare at a maximum speed of 60km/h, it was a relief to get on the motorway and drive that Fiat in the general direction of Limerick City at exactly 120km/h.

Limerick, a city founded on an island where the Shannon empties into the Atlantic, has had many names over its long and chequered life: it was known as Hlymrekr to the Vikings who torched the place in 812; in Gaelic it’s Luimneach or, formerly, Inis an Ghaill Duibh (“dark foreigner’s island”); Stab City to those who disparage it; and Treaty City to the promoters of the city’s history of wars and peace.

To be honest I knew nothing of this history when I arrived in Limerick: all I had in mind as I pulled up to my eye-wateringly expensive hotel accommodation was to do some handwashing in my room and then try to make contact with the County Limerick equivalent of the Clare Generalogy and Historical Centre, whose details A— had passed on to my during our meeting in Corafin that morning.

Having hung up my clothes to dry in my well-appointed bathroom, I opened my laptop and filled in a form on the Limerick Genealogy website, requesting information about my great-great-grandparents. I was only half-expecting a reply but within an hour had set up an appointment for the following day with C—, a genealogist working out of Croom, 20 kilometres south of Limerick City.

LESS THAN TOTALLY INCORRECT • Croom is a non-descript town with a little river running through it, 20 kilometres south of Limerick City. The Limerick Genealogy offices are located in the riverside community centre. I met C— there at 10am, as arranged. A softly spoken and friendly woman about my age, she presented a different vibe to my interlocutor in Corafin, and I had a good feeling feeling as we entered her office on the first floor.

Of course, this good vibe probably had more to do with my preparation for the meeting than anything about C— personally. Based on my “discovery” about the place where my great-great-grandparents were married, I had been able to provide her with a relative wealth of information compared to the meagre—and totally untrue—origin story I had sought to pass off to A— as genuine.

And to be very honest, the story my mother told me about our Clare origins was only wrong in one respect. Sure, that ‘respect’ was pretty a pretty crucial one, but the rest of it—which I will reveal in good time—turned out to be less than totally incorrect, if not 100% correct, either. And, crucially, I totally ignored the part of the story she told me about poor Richard, whom I will get to presently.

WINDOWS • C— invited me to sit down next to her at a desk with nothing on it except a modern Windows computer. The screen was switched on and displayed, in a browser, the web form I had filled in the previous day while waiting for my smalls to dry. Looking back at it now, it’s amazing to think what I had learnt in the space of a few hours—literally driving ninety down the highway towards my ancestors.

I had started by listing my great-great-grandfather’s name: William Hurley. I also knew his approximate date and place of birth, the date of his marriage, and the details supplied by J— about his emigration to Australia. More than that I was unable to state then—and the sad truth is that I still know little more about William now. Even his own death certificate lists none of these facts, apart from his name.

However, I was in possession of more facts about my great-great-grandmother, Johanna Fitzgerald, and I have since come to learn so much about her, and her family. And for these insights I owe a particular debt of gratitude to C—, for guiding me through the maze of West Limerick genealogy and history, and for doing so in such a gentle and pleasant way.

“You’ve already come so far,” C— said, reassuringly, as we sat there looking at the computer’s screen.

I very much wanted to agree with her. But, of course, I had only just begun. Over the course of the next four hours that screen would become populated with window after window into the past.

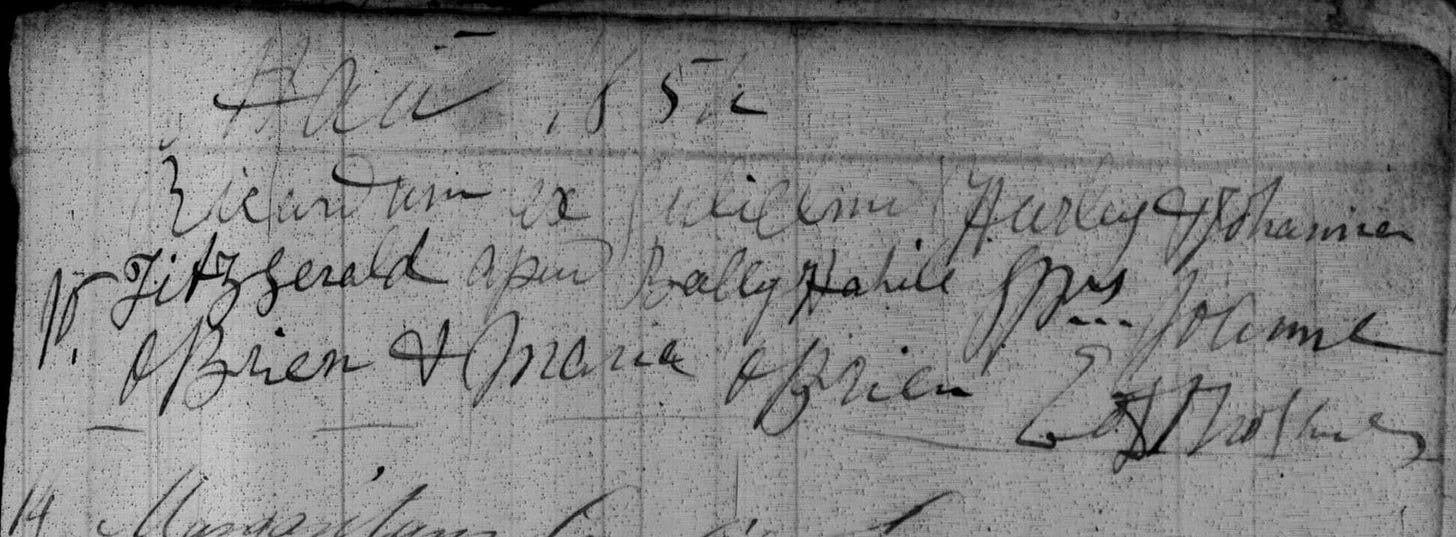

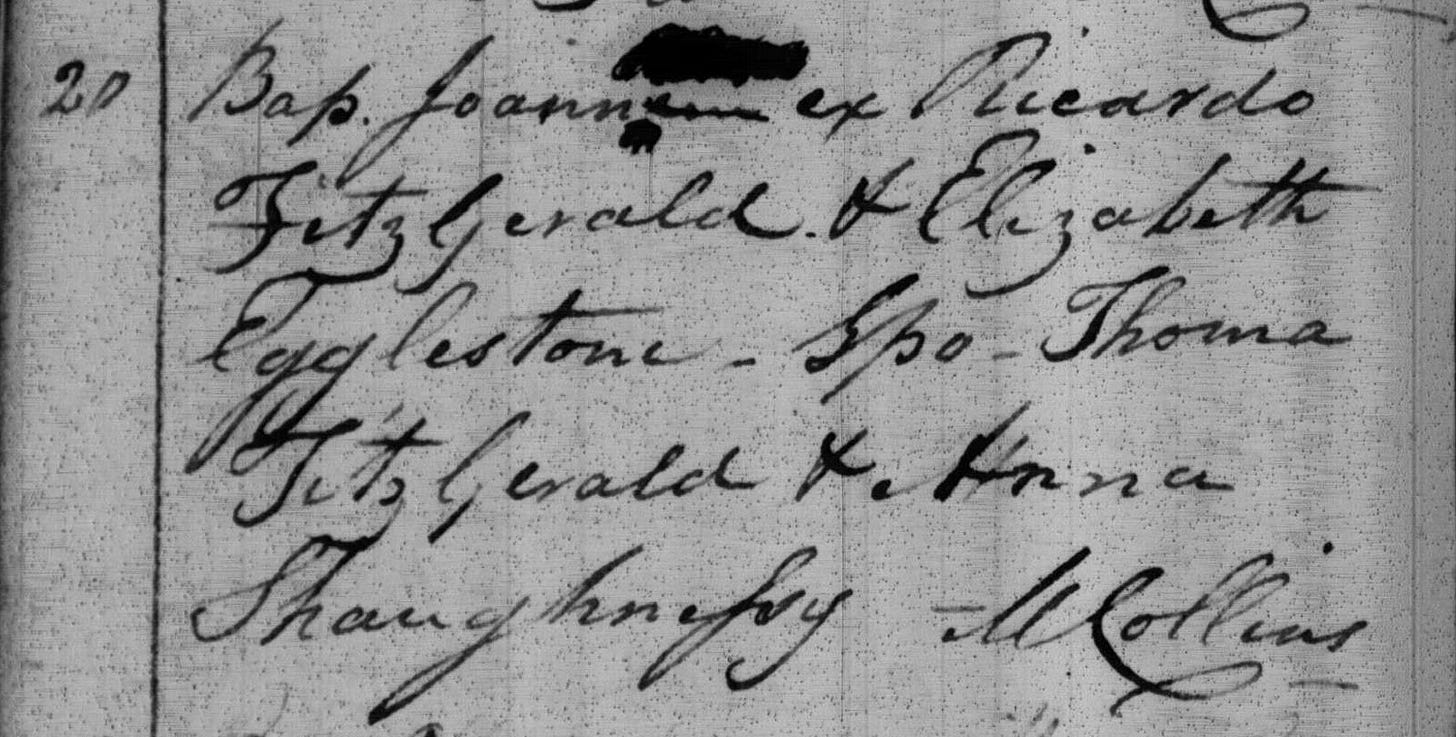

It turned out that C— had already done some digging through the archives on the basis of the form I filled in, and had found both William and Johanna’s birth records—or, at least, what looked like the birth records of two people who later married in Ballyhahill, West Limerick, had a child named Richard but left him behind as an infant, promising to return from Australia but never quite managing to do so.

His may be the only story that I was literally born to tell.

POOR RICHARD • My father had one job on the day I was born: to go to the registry in Dubbo and record the details of my birth. No doubt they also had a form for him to fill out there, making it easier to get the basic facts right. It will come as no surprise to anyone that one of the most important of these facts is a person’s name. But there was just one problem: according to my mother, at least.

“I have been searching for missing ancestors,” I informed her, airily, about a year after I got back from my trip to Ireland, during a meandering, multi-day WhatsApp conversation that included musings on Australian novelist Charlotte Wood, Robert Hughes’ The Fatal Shore, and updates on the scores in completely fictitious cricket tournaments.

“Who’s missing?” mum asked.

“Think I might have found Richard,” I replied, inserting a gratuitous LOL. “The one they left behind.”

“Right,” mum wrote. “You were supposed to be named after him.”

Wait, what??

“You were supposed to be Richard John,” mum insisted, “but Carlton draft was on tap in Dubbo that night and dad couldn’t remember the name so filled out the registration papers as he saw fit!”

Only it gets worse.

Because not only did my father forget—or perhaps flat-out refuse—to call me Richard John, he actually registered me as David John. Then promptly returned home and informed my mother that he’d called me David Thomas. And this is the name that appears on my baptismal certificate, which has no legal value whatsoever but is at least something to hold onto. A curio, if you like.

It wasn’t until some 17 years later that we discovered dad’s category error, when we requested a copy of my birth certificate as part of the process of getting my Higher School Certificate. I’ll never forget the look on his face when he opened the letter from the NSW Births, Deaths and Marriages people, and saw the name David John where we’d always assumed David Thomas should be.

“I can always change it legally,” I told mum in 2024, after she dropped her bombshell.

“You’ll always be Richard to me!!” she replied.

While I knew nothing of this story in Croom, as C— showed me how to decipher the parish records from mid-1800s West Limerick, it’s difficult not to appreciate the contrasts. While my great-great-grandparents’ birth records were scribbled in a mix of Latin and English by elderly Catholic priests with bad handwriting, their Australian death records were immaculate, cursive and readable, even to me.

Similarly, while my baptismal certificate featured both handwritten script and standard typed elements, my birth certificate was completely typed, and it was a disturbingly simple process to have it amended to state that I had always been known as David Thomas. Even though I had always been known as someone else, to both of my parents, at literally the same time.

Poor Richard, I thought. Maybe he never existed either.

THERE SHE IS • One of the (many) things that make searching for lost Irish ancestors difficult is the number of errors introduced by well-meaning efforts to transcribe and digitise records of births, deaths and marriages—especially Catholic ones. My great-great-grandmother’s are no expection: Roots Ireland records exist for ‘Hana”, “Johan” and “Judith”. Only one of them can be her.

But which one?

Similar errors can be found elsewhere, too. The transcript of the passenger list for the Fitzjames, the ship on which William and Johanna Hurley emigrated to Australia in 1855, states that their place of residence was Somerset, England. A closer look at a scan of the actual passenger list (PDF) reveals, surprisingly enough, that someone (or perhaps even an OCR program) had inserted ‘Somerset’ instead of ‘Limerick’.

And it’s this kind of error (or translation: I don’t really see much of a difference) that makes genealogy less a science and more of a journey of interpretation: because as we will soon come to see, the ghosts of my ancestors continue to exist in several dimensions. An essential part of the journey towards them involves recognising and working back from errors, wild goose chases and cases of mistaken identity.

Meanwhile, back in Croom, C— was having more success finding traces of the Fitzgerald side of the family. Unlike the Hurleys, of whom very few traces survive post-1855, the Fitzgeralds remained in Ballyhahill long after William and Johanna emigrated to Australia. And it seems likely that Richard, who was 18 months old when they left, ended up living with Johanna’s mother, Elizabeth Fitzgerald.

Elizabeth is one of the most fascinating characters I’ve never met. It appears that she (and her sons) ran the store in Ballyhahill after her husband’s death, and the family remained local until the mid-20th century. She is mentioned in the tithe books for the town, and of course in the birth records of her children, although there is no record of her own birth or the death of her husband, another Richard.

C— spent some time with me searching the online databases for references to Elizabeth. About three hours into our consultation, having booked an hour of her time, I was beginning to feel guilty. But she did not seem to mind, instead taking genuine pleasure in helping me. Finally, she let out a tiny gasp, leaned forward and pointed to a record on the screen.

“There she is,” C— whispered softly, and my heart nearly broke.

It was a civil death record, stating that Elizabeth had died of old age on 13 January 1879—and an astonishingly old age it was, too: 87, no less! She was listed as a widow, and a shopkeeper’s wife, and may well have died alone. There is no record of her grave, however, and no graveyard in Ballyhahill to speak of in any case.

What became of her?

And what of her life with poor Richard, her grandson, named in honour of her (possibly deceased) husband?

There was only one way to answer these questions. After thanking C— profusely and promising to send more money to compensate her for the additional time, I jumped back in the Fiat and drove straight to Baile Dhá Thuile, the town known in English as Ballyhahill. When I got there, I planned to visit the church where William and Johanna were married, and then perhaps pay a visit to the village store.

Who knows, maybe someone there would remember the Fitzgeralds.

And even if they didn’t, at very least I could buy something.

A trifle, for example.

Yes, a trifle would do very nicely, indeed.

Loving the serialised drama!

You have also blessed us with the phrase “linguistically ripped frame” which I will now incorporate into daily conversation.

So sad that poor Richard was left behind!! 🥲🥲.