On Archie Moore, Kamberri and family trees

A trip to Australia's national capital changed my views on genealogy

In November 2024, I spent 48 hours on the land of the Ngunnawal people in Australia’s national capital, Canberra. In the 1990s I lived in this beautiful garden city for a year while working for the federal public service, and have revisited it many times since. But my interactions with national institutions and narratives made this trip meaningful in new and unexpected ways.

I arrived in Canberra (sometimes spelt Kamberri) from Melbourne around noon. Having faced a choice between driving, catching an overnight train or flying, I’d opted reluctantly for the latter but was pleasantly surprised to find, on arrival, that the public bus from the airport to the city was both frequent and free, a by-product of delays in the public transit authority’s introduction of a new ticketing system.

In fact, all public transport in the city was free for the duration of my visit, and in hindsight this had a profound effect on what I did and saw. Although it was still spring, daytime temperatures hovered around the 28-30 degrees Celsius mark, and while the sadist in me was tempted by the idea of riding a bike around, it was a relief to be able to get on an air-conditioned bus and get practically anywhere in 15 minutes.

The city of Canberra was established in 1913, making it a very young capital in so-called historical terms. But to dwell solely on this settlement-flavoured narrative would be to neglect the fact that the area where Canberra is situated has long been inhabited, and cared for, by First Nations peoples including the Ngunnawal, Ngunawal and Ngambri peoples. I pay my respects to their Elders past and present.

Now, I hadn’t come to Canberra for a holiday. However, while it’s not the most touristic city in the country, Canberra is home to a number of national institutions, including the National Gallery of Australia (NGA), the National Library of Australia (NLA), and the Australian Museum. I visited all three during my stay, searching for answers but also open to new questions, new ways of knowing.

Having arrived in Civic, Canberra’s understated equivalent of a central business district, I jumped straight on one of the city’s brand-new trams for a quick dash up Northbourne Avenue to my accommodation, a suitably spartan single room in a former student digs run by the Australian National University. I could write a whole post about Canberra’s trams, but will spare you that fate for now.

With a full half day ahead of me, the sun blazing and the sky an outrageously edible blue, I rehydrated, changed into shorts and sandals and then walked back into Civic via the backstreets of Braddon. When I lived here 30 years ago, this was a rundown area of auto repair shops and service stations; today, the streets are lined with cafes, outdoor pubs and bespoke clothing shops. Clearly, much has changed.

But then again, it’s heartening that some things remain immutable. I mean, catching a bus to the NGA from the Civic bus terminal still takes the same amount of time, and my confusion about where exactly to get off led to a fifteen-minute backtrack on foot via various obscure national institutions related to the military and economics. Anyway, when I reached the NGA forecourt, something clicked. I knew this place.

Of course, nothing could have prepared me for the impact of seeing Lindy Lee’s stupendous Ouroboros (2024) parked out front of the NGA like a visiting spaceship. And while the main hall of the NGA itself is still dominated by The Aboriginal Memorial (1988), Archie Moore’s Family Tree (2021), hanging in the same space, shocked me out of my complacency and changed the way I think about genealogy.

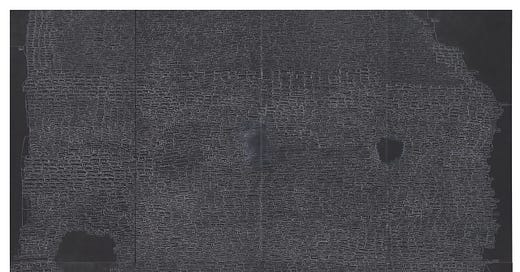

Moore is a Kamilaroi/Bigambul artist who recently represented Australia at the 2024 Venice Biennale with his work kith and kin, a massive family tree drawn in white conté on blackboard paint that covered the walls (and ceiling) of the Australian pavilion. Writing for the ABC, Daniel Browning described the work as “what must be the most expansive family tree ever drawn by hand”.

Family Tree and kith and kin are related works. As Moore himself notes, “Well there’s three versions of it now, but they all involve blackboard paint on a panel of some material, or just a wall.” Crucially, Family Tree is not immediately visible when one enters Gallery 9 at the NGA, and one almost needs to navigate The Aboriginal Memorial in its entirety before Moore’s network of names on the wall comes into view.

Perhaps this is intentional: The Aboriginal Memorial is unlike any other artwork I’ve had the privilege of interacting with. The NGA’s first director, James Mollison, described it as “probably one of the greatest works of art ever to have been made in this country”. Its 200 painted ceremonial coffins constitute a map of Central Arnhem Land in Australia’s far north and, in the words of Djon Mundine, “a war memorial”.

I’ve probably experienced this installation half-a-dozen times but seeing it in November and then ‘discovering’ Archie Moore’s Family Tree on a wall in the same gallery just hit differently, somehow. It’s hard to explain but maybe what I’m trying to say is that, this time, I was different, too. The person I was when I entered that space was not the same as the version of me who came here in 1992, or 2007.

I’d arrived in Canberra this time after spending five days investigating aspects of my own family history on the Mornington Peninsula south of Melbourne/Naarm. Part of those investigations involved conducting archival research in the State Library of Victoria, as well as first-person interviews with my mother and two of my aunts, who may well be the oldest living members of my own family.

Seeing and experiencing Moore’s gargantuan statement on the history of Indigenous dispossession and endurance obviously put my efforts into some sort of context. But I don’t mean to necessarily suggest that I felt some kind of competitive jealousy, or a sense of my own history’s overwhelming triviality (although both reactions remain valid); rather, I felt a quiet sense of interconnection.

Moore appears to have been on something of a personal odyssey when it comes to recovering and documenting his own family history. He describes the process in terms that will be familiar to genealogists everywhere:

Looking at a family tree, researching it for, like over four years now on that ancestry site, building a tree, looking at the archives, finding information about family members, trying to work out how I became to be here kind of thing.

— Archie Moore, on Family Tree (2021).

While I love the almost offhanded reference to “that ancestry site” (although the quoted text is a transcript of an audio clip, in which Moore might only be saying “the ancestry site”), it’s the idea of “building a tree” that strikes me as vital, even as I type these words half a world away in a place where there are no trees, the seasons are treacherous and the temperature never, ever gets to 28 degrees Celsius.

Because, when placed in the context of an installation of hollow-log ceremonial coffins commissioned for the bicentenary of the invasion and occupation of Australia, an artwork that echoes the process of “building a tree” is both a puzzle and an act of defiance. Like Lindy Lee’s Ouroboros, its end is in its beginning; its smudges of blackboard marker gesturing towards spaces where the disappeared have names.

Moore’s family trees are designed to overwhelm, but also to inspire wonder: in a video explainer, he talks about how the names written on the ceiling of the Venice Biennale pavilion represent the stars of the night sky, and his ancestors. Zooming back to the NGA, I noticed that Moore represents himself in Family Tree by way of a handwritten “Me” at the very bottom of his vast installation.

Having immersed myself in angular, linear representations of family, I found this gesture both moving and humble. Maybe this is the place to start: from an awareness that each of us, eventually, could trace our own family lines back to a common ancestry. The kind of ancestry that’s not just a “site” but a living organism: an actual tree, built by art, on which people’s lived lives are so much more than mere leaves.

DD, this morning was the final walk of the Victorian Yoorrook Walk for Truth. One of the Djirri Djirri dancers talked about the importance of grandmother trees. I won’t do it justice and will try to find a link for you. This post made me think of it